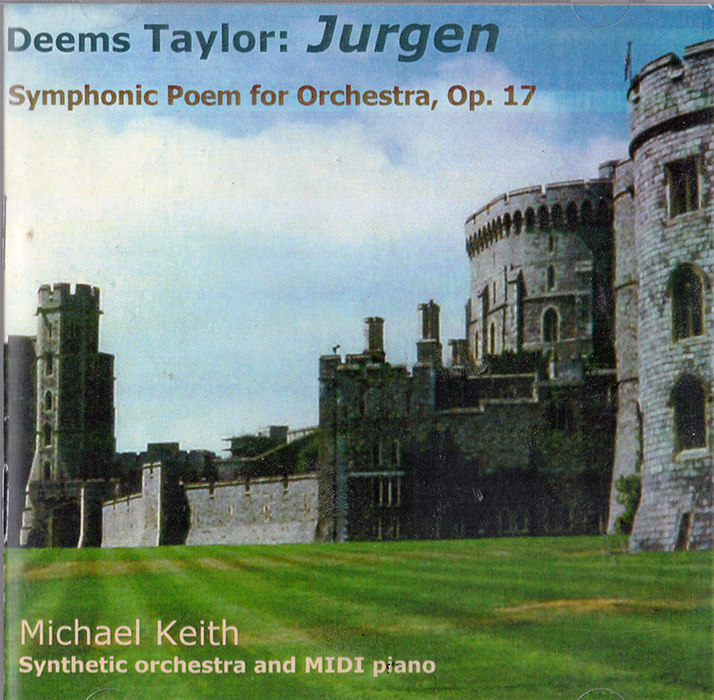

In 1999, Michael Keith was awarded the second annual Cabell Prize for his liner notes and performance of Deems Taylor’s Jurgen: Symphonic Poem for Orchestra, Op. 17 and Jurgen: Arrangement for Piano Four Hands. The recording was produced using Roland and Kurzweil synthesizers (standing in for an orchestra) and a Kurzweil digital piano.

In 1999, Michael Keith was awarded the second annual Cabell Prize for his liner notes and performance of Deems Taylor’s Jurgen: Symphonic Poem for Orchestra, Op. 17 and Jurgen: Arrangement for Piano Four Hands. The recording was produced using Roland and Kurzweil synthesizers (standing in for an orchestra) and a Kurzweil digital piano.

According to Keith’s notes, Jurgen, Op. 17, is scored for string section plus flutes, piccolo, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contra-bassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, a harp, and a percussion ensemble consisting of three timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, glockenspiel, xylophone, and celeste. The composition is structured in six sections, which are played together without a pause.

Presented here are excerpts from Keith’s work: an audio selection of the “Love Theme” from Jurgen, and a portion of the recording liner notes. The full recording and liner notes, along with Keith’s recording of another Cabell-inspired work — Louis Cheslock‘s Overture from The Jewel Merchants — are available through VCU Libraries Digital Collections.

These works are the first recordings of both the Taylor and Cheslock compositions; neither piece has ever appeared on a commercial recording. Sound recordings and liner notes are protected by copyright, and copyright is owned by Michael Keith.

“Love Theme” from Jurgen: Symphonic Poem for Orchestra, Op. 17

Composed by Deems Taylor (1925); recorded by Michael Keith (1999).

Excerpted liner notes:

“I have finished Jurgen; a great and beautiful book, and the saddest book I ever read. I don’t know why, exactly.

The book hurts me – tears me to small pieces – but somehow it sets me free. It says the word that I’ve been trying to pronounce for so long.

It tells me everything I am, and have been, and may be, unsparingly…

I don’t know why I cry over it so much. It’s too – something-or-other – to stand.

I’ve been sitting here tonight, reading it aloud, with the tears streaming down my face…”

Deems Taylor, Letter to Mary Kennedy, 12 Dec 1920

“For I am transmuted by time’s handling

I have become the lackey of prudence and half-measures;

and it does not seem fair, but there is no help for it.

So it is necessary that I now cry farewell to you, Queen Helen:

for I have failed in the service of my vision, and I deny you utterly!”

Thus he cried farewell to the Swan’s daughter…

And to Jurgen the world seemed cheerless and

like a home that none has lived in for a great while.

James Branch Cabell, Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice, end of Chapter 47.

Fans of Richmond, Virginia author James Branch Cabell’s rollicking yet philosophical adventure Jurgen, published in 1919, have waited 73 years for this, the first recording of distinguished American composer Deems Taylor’s Symphonic Poem for Orchestra based on Cabell’s novel.

Jurgen was commissioned by Walter Damrosch and the New York Symphony Orchestra, and first performed in Carnegie Hall on 19 November 1925. It was heard a few times thereafter but then, except for a brief revival twenty years later in a slightly altered form (called Fantasy on Two Themes), more or less disappeared. For instance, a four-page article on the music in the Autumn, 1970 issue of The Cabellian – one of two scholarly Cabell “fanzines” that have had a run over the years – can do little more than quote from announcements and reviews of the performance and admit a complete lack of knowledge as to the contents of the piece.

Deems Taylor (1885-1966) was one of the most widely known, versatile composers and music popularizers of his day. Today he is often remembered for his orchestral suite Through The Looking Glass (available as of this writing on a CD by Gerard Schwarz and the Seattle Symphony) and for being the narrator in Walt Disney’s film Fantasia. Besides Through The Looking Glass, which is based quite closely on Lewis Carroll’s classic, Taylor composed several other pieces of “program music”, such as Circus Day, which depicts in very successful fashion the many facets of a day at a small-town circus. Taylor also wrote several successful choral works, and his perceptive, witty music criticism for The New York World made him one of the most famous music men in New York.

Taylor’s composing years peaked in 1925 with three commissions: the first commission ever by the Metropolitan Opera (resulting in The King’s Henchman, with libretto by Edna St. Vincent Millay), a commission by the King of Jazz, Paul Whiteman, for his concert orchestra (resulting in Circus Day), and, finally, the commission by Walter Damrosch which led to the composing of Jurgen.

James Branch Cabell’s novel Jurgen, which is actually part of a massive eighteen-volume whole referred to as The Biography of the Life of Manuel, is the most famous of his fifty-odd books. It is justly renowned as a masterful novel, though its notoriety was increased manyfold by being briefly banned in the early 1920’s by The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Jurgen was a book in many ways ahead of its time, not for the mild sexual innuendo which resulted in its suppression, but for its sardonic, cynical commentary on everything from the vagaries of love to the tenets of religion. The reader who has not experienced Jurgen is encouraged to do so – immediately, if not sooner! – as it is still in print and easily obtainable. Here, in the meanwhile, is a brief summary.

Thanks to a kind word in defense of the Devil, and a subsequent visit to one Mother Sereda (of which more later), Jurgen, a middle-aged pawnbroker married to a woman named Dame Lisa (who has “no especial gift for silence”), finds himself gifted with a year of life in possession of his twenty-year-old body – but still his somewhat disillusioned forty- year-old mind. Thus he sets out, from his home in Cabell’s land of Poictesme, on an adventure through many imaginary, even mythological, lands, including King Arthur’s Britain, the land of the Philistines, the Hell of his father and the Heaven of his grandmother – both of which, it turns out, are mere inventions by the great Koshchei The Deathless, “who made all things as they are”.

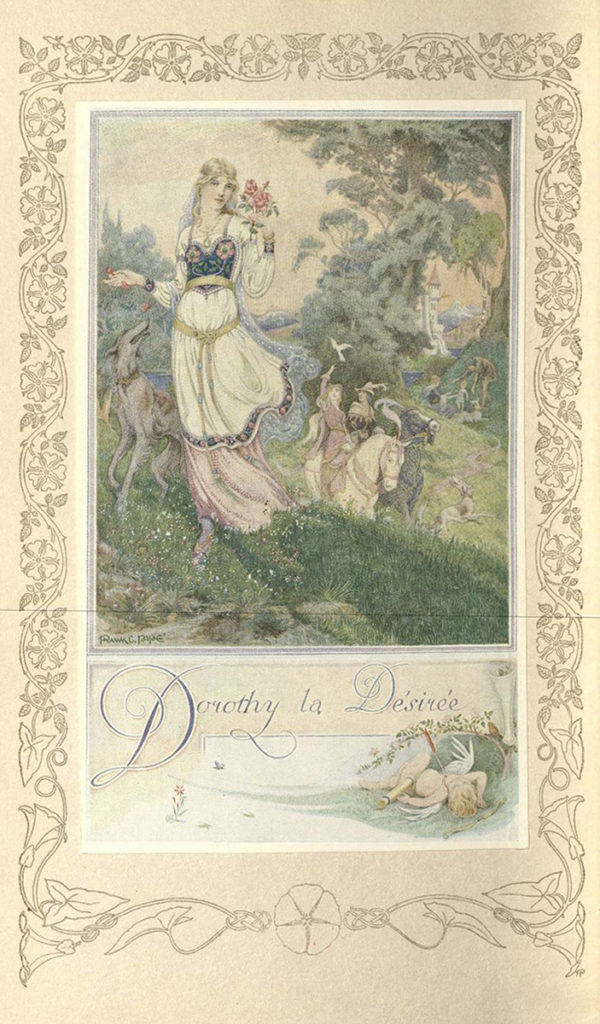

frontispiece, Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice

A central theme in the book is Jurgen’s desire to reclaim the love of his youth, represented by the encounters during his travels with three women: Guenevere, Queen Anaïtis, and the famous beauty Helen. During Jurgen’s adventure he is also thrice married, thus mirroring his situation in the present, where he is married to Dame Lisa but sometimes – frequently? – thinks wistfully of Dorothy La Désirée, “the only woman whom I ever loved”. This is highly autobiographical, referring to Cabell’s youthful relationship with a woman called Gabriella Moncure. Though Cabell was twice married, he carried a flame for Gabriella—the only woman he ever loved romantically—for decades. The astute reader of Jurgen will find therein numerous references to this defining incident in Cabell’s life; for example, in Chapter 29 he refers in song to one of his loves as “Heart o’ My Heart”, a punning reference to Moncure = mon coeur = “my heart”.

In the program notes for the first performance of Jurgen, Taylor writes as follows:

Jurgen was originally planned as an orchestral suite that would follow as faithfully as possible the sequence of events in James Branch Cabell’s book; but when I started work on the music, it became increasingly obvious that such a program was not only impracticable but hardly to the point. It would take a cycle of suites to do adequate justice to the bewildering multitude of scenes, characters, and episodes with which the pages of Jurgen are crowded. Moreover, the importance of Cabell’s romance as a work of art lies, not in its qualities as a diverting tale of amorous adventure, but in the vividness, the sardonic gusto, the humor and wisdom and pathetic beauty with which the tale is told. So Jurgen, annotated in terms of music, has come to be concerned much more with Jurgen than with his deeds. There is no definite story…

In brief, I have tried to show Jurgen facing the unanswerable riddle of why things are as they are; Jurgen, ‘clad in the armor of his hurt,’ spinning giddily through life, strutting, posturing, fighting, loving, pretending; Jurgen proclaiming himself count, duke, king, emperor, god; Jurgen, beaten at last by the pathos and mystery of life, bidding farewell to that dream of beauty which he had the vision to see, but not the strength to follow.

We see from this description that it is hazardous to attempt to interpret Taylor’s tone poem too literally in the light of Cabell’s novel; still, Taylor gives some hints as to what the main themes represent, and there are several other features that bear such close resemblance to aspects of Jurgen, the book, that they can hardly pass unnoticed.

© 1999 Michael Keith