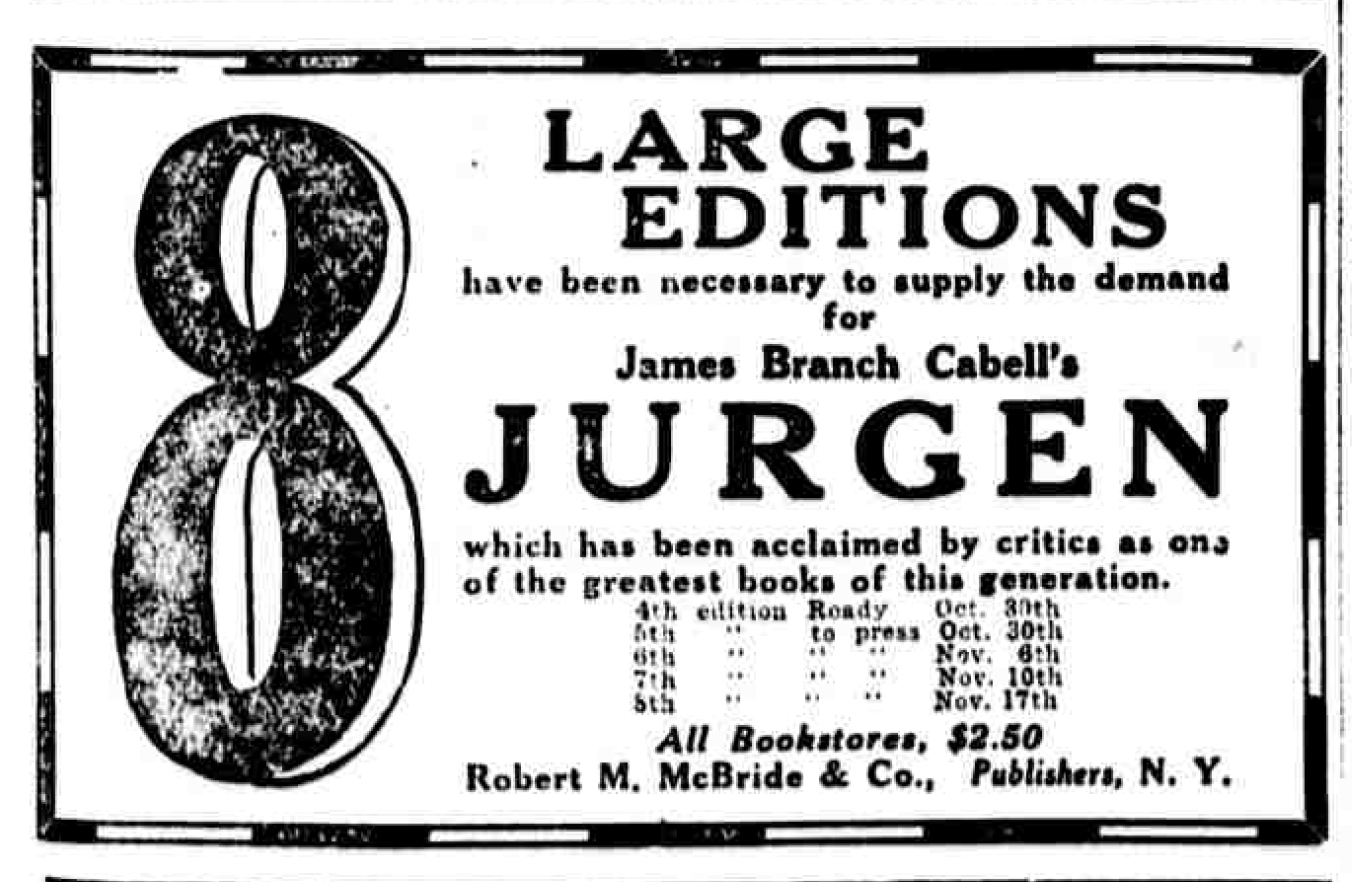

In the aftermath of the dismissal of the indictment against defendants Robert M. McBride & Co. and editor, Guy Holt, sales of Jurgen were brisk.

The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice continued its crusade against obscenity, despite protest and controversy. On November 8, 1922, only weeks after the case against Jurgen was dismissed, the National Arts Club hosted a debate between John S. Sumner, NYSSV, and Carl Van Doren, literary critic. It was reported in the New York Tribune the following day.

The following excerpts are transcribed from reporting of the debate in the New York Tribune, Nov. 9, 1922, p. 11.

Sumner Hints Bad Book Led to Hall Murder

Vice Crusader, Hand Resting Unwittingly on Copy of ‘Jurgen,’ Faces Critics and Assails Prurience

Denies He’s for a Censor

Carl Van Doren Replies that Public No Longer Thrills to Naughtiness.

The profound questions of whether modern literature should be pure or prurient, and who has the right to determine which is which, and why, engaged the attention of some 300 literary lights of New York City, mostly women, in the National Arts Club last night.

It was a debate on “Propriety and Impropriety in Literature,” with John S. Sumner, secretary of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, as the principal upholder of best seller regulation, by force if necessary, and Carl Van Doren, literary critic, as the main proponent of the belief that societies for the suppression of vice should find something better to do than stop authors from getting true expression into their art, or vice versa.

Mr. Sumner, who declaimed with his left hand resting unwittingly on a copy of “Jurgen” before him on the speakers’ table, defended the existence of his organization chiefly on the ecclesiastic theory that most people, including book publishers, are constantly doing foolish things, and that some one ought to be on hand to save them from their own folly. The society, he contended, filled the bill in that respect for authors and publishers, and therefore should be praised rather than panned. He declared the society did not seek to establish a censorship over literature.

After quoting the laws bearing on obscene publications, he went on to criticize recent decisions of New York judges upholding books condemned by the society, notably the cases of “Jurgen” and “Satyricon,” implying the jurists had disregarded the proper legal procedure in reaching their findings. In connection with “Jurgen,” he took occasion to criticize Burton Rascoe, literary editor of The Tribune, for the latter’s praise of the book, saying “it was dedicated to him….”

Mr. Van Doren’s main line of attack on Mr. Sumner’s remarks was to the effect that if a book is offensive public opinion will discover the fact soon enough and reject it, and that therefore the existence of extra legal bodies for the purpose is unnecessary. The folk regard for good taste was a sufficient restriction for authors he declared.

“I could not, for instance, tell a naughty story here and get away with it,” he said.

He urged Mr. Sumner to turn his attention against “imbecility in literature,” which, he said, was far worse for the public than naughtiness.

Other speakers were…Mary Austin, novelist and playwright, who spoke of complexes, and looking hard at Mr. Sumner told him that the backers of his society ought to get after some of the “anything-goes-provides-she-saves-her-honor” books to be found in their own libraries, rather than after such books as “Jurgen,” which she defined as “a collection of Pullman smoking compartment stories which you may or may not listen to, as you choose.”

“The novel, ‘Jurgen,’ published in 1919, and its censorship in New York and Boston made Mr. Cabell famous. He later noted, however, that he did not care to be remembered by that novel.”

The suppression of Jurgen boosted James Branch Cabell’s career tremendously, bringing international fame and selling a great number of books. As the public clambered for the story, other writers adapted Jurgen for the stage and for radio. Deems Taylor composed a symphonic poem. Modern dance pioneers Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis choreographed a dance version. Eventually there was a movie treatment, and even a script for Jurgen: A TV Musical.

But along with the expanded audience and opportunity brought about by Jurgen, the book also brought with it constraints. Cabell became known to the public as “the author of Jurgen,” or was labelled a fantasy writer, or perhaps worst of all, remembered as “the author of that smutty book.” His later, most accomplished novels never achieved the same level of recognition as the work that had been accused of being lewd, lascivious and indecent.

After concluding his 18-volume Biography of the Life of Manuel in 1932, Cabell ceased to write about Dom Manuel and Poictesme and began writing under the professional name “Branch Cabell.” Eleven books were published under that name before he returned to writing as James Branch Cabell with There Were Two Pirates: A Comedy of Division in 1946.

In his biography of Cabell, Edgar MacDonald reports that the author allowed that the Storisende Edition might have been a mistake, because it “equated his best work with the inconsequential” (MacDonald, p. 346). After 1932, James Branch Cabell never again wrote a novel set in Poictesme. His final work, As I Remember It: Some Epilogues in Recollection, was autobiographical and had as its epigraph a quotation from Tennyson’s “Ulysses:” “I am a part of all that I have met.”

Jurgen and the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice

The Judging of Jurgen by James Branch Cabell (1920)