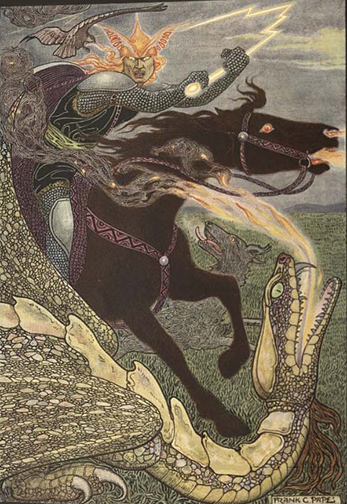

Richard Wilson, Illus. Frank C. Papé.

The Cabell Room, Special Collections and Archives, VCU Libraries

James Branch Cabell was a shy, bookish youth who grew into an accomplished writer with a personal library of nearly 3,000 volumes. His reading interests were broad, and his library included voodoo, folklore, occult subjects, mythology and anthropological studies, classical literature, works by literary peers, popular mysteries, poetry and books on love, sex and marriage. Some of these books were gifts from his uncle, Dr. Arthur Cabell, a navy physician and world-traveler. Many were gifts from family, friends and literary associates.

As a student at The College of William and Mary, Cabell excelled at languages, earning Certificates of Distinction in French, Greek, Latin, English and German. He was greatly interested by literary and poetic forms and devices. He delighted in the classics and in troubadour poetry of gallant knights and unattainable women. Later, as a writer, Cabell would draw from these literary sources, quoting and alluding to classical authors and characters from mythology and legend, and creating his own fictional medieval French province, Poictesme.

James Branch Cabell is often described as a fantasy writer and an ironist, but those terms, however appropriate, fail to encompass the nature of his artistic endeavors. Cabell called his works “comedies” and “dizains,” and wrote approvingly of the romance as an imaginative literary form, which he distinguished from the dull, “photographic” novel of contemporaneous happenings. In this respect, Cabell’s fiction provides a counterpoint to twentieth-century works of realism and to the Southern Renaissance.

Because Cabell draws from so many sources, and because he was interested in literary forms that may be unfamiliar students and general readers, a few useful terms that appear in connection with his fiction are given below.

Comedy — Thirteen of Cabell’s books contain the word “comedy” in their titles, establishing the naming convention that is most closely associated with the author.

Cabell used comedy in its specialized literary sense. More than a funny story, a comedy can be a medieval narrative that ends happily; a drama that treats a serious subject in a light or satirical fashion; or, a narrative that amuses the reader by making them feel superior to the characters. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms adds that a comedy is likely to be closer to the representation of everyday life than a tragedy. Comedy may use stock characters. A comedietta is a brief comedy, or a dramatic sketch. See for examples: Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice; The Cream of the Jest: A Comedy of Evasions; and The Way of Ecben: A Comedietta Involving a Gentleman.

Dizain — a French verse stanza of 10 lines, typically with 10 syllables per line. Cabell used the word dizain in the title of several of his books which were collections containing 10 essays or stories. See for example: Gallantry; An Eighteenth Century Dizain in Ten Comedies, with an Afterpiece; Straws and Prayer-Books: Dizain des Diversions; and Beyond Life: Dizain des Demiurges

A rondelet is French poetic form with seven lines, of which three are refrains. The rondelet is a modified form of the rondeau, a type of trouvère song.

Troubadours were poet-musicians of Provence during the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries. They celebrated chivalry and courtly love. Bertran de Born was a troubadour admitted to the court of Eleanor of Aquitaine in northern France. Northern French troubadours were also called trouvères.

Courtly love — a medieval conception of love first popularized by the troubadours. Courtly love sets out appropriate behavior for chivalrous knights, noble lords and ladies. According to The Reader’s Encyclopedia (William Rose Benét, 2nd ed. 1965. vol 1 p. 230), “Courtly love “postulates the adoration and respect of a gallant and courageous knight or courtier for a beautiful, intelligent, lofty-minded noblewoman who usually remains chaste and unattainable. He performs noble deeds for her sake, but suffers terribly because she remains indifferent or, even if she favors his devotion, because her purity and his respect for it prevent the consummation of their love. … Nevertheless, the lover welcomes the suffering of his passion, for it ennobles him and inspires him to great achievements.”

Domnei — Old Provençal term meaning the attitude of chivalrous devotion of a knight to his Lady. See: Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship.

Provençal — Provençal is the name given to the older version of the Occitan language (Old Occitan) used by the troubadours of medieval literature.

Romance (ro-MANCE as opposed to RO-mance) refers to an adventure story filled with marvels and wonders that follows a hero of chivalry, and involves courtly love. In medieval literature, romances were originally written in Old French or Provencal. From the late 18th century onward, the term romance refers to prose fiction where the story is mysterious or strange, removed from everyday life. Romance is often seen as opposed to realism. See “Romance and the Novel” James Branch Cabell’s review of E. R. Eddison’s Mistress of Mistresses in The American Mercury January 1936. A letter from Cabell was printed with the first American edition of Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, a heroic fantasy read and praised by J. R. R. Tolkein. See also, this article in Kalki: Studies in James Branch Cabell (vol 2, no. 4) courtesy Thorne and Lloyd.

Realism — realist authors choose to depict everyday people and experiences accurately, without artificiality or supernatural elements. Realism represents a turn away from Romanticism.

Modernism — a literary, artistic, and philosophical movement arising in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism developed in a time of increasing industrialization and urbanization, technological invention, and mechanized global warfare. Literary modernists experimented with new forms of expression and new subject matter. T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Marianne Moore and Virginia Woolf are among many considered modernist writers. American modernism was a dominant literary movement between World War I and World War II when most of Cabell’s works were published.

Satire — a literary work employing wit, sarcasm, irony or exaggeration to hold up human vice or folly to scorn. Satirical literature can be categorized as either Horatian, Juvenalian or Menippean, depending on how how caustic the criticism (savage ridicule and insult, or gentle chiding), and whether the work criticizes individuals and entities (e.g., a government) or attitudes and beliefs (e.g., “this is the best of all possible worlds!” in Voltaire’s Candide or “Everything is Awesome!” from The Lego Movie.) Some of Cabell’s writing been described as Menippean satire.

Parody — imitation of the style of a particular writer, artist or genre with deliberate exaggeration for comic effect Pastiche also imitates the style or character of the work of one or more other artists, but unlike parody, pastiche celebrates, rather than mocks, the work it imitates.

Irony — a literary device using words to express something other than, and often the opposite, of their literal meaning. Scholars distinguish numerous types of irony, such as classical, cosmic and dramatic irony. James Branch Cabell’s ideas about the universe and humanity’s experience of life cannot be understood without a firm grasp of this concept.

Anagram — a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of a different word or phrase. A type of wordplay or puzzle. Cabell enjoyed wordplay and hidden meanings. In Something About Eve: A Comedy of Fig-leaves, the hero, Gerald Musgrave, travels through Doonham, Dersam, Lytreia, Turoine, Mages and Mispec Moor–all of which are anagrams. (“Mispec Moor” is an anagram of “compromise,” for example.)

Epigraph — a quotation set at the beginning of a work or a chapter of a work that suggests its theme. Cabell’s epigraphs are both eclectic and revealing.

Sigil — a seal or signet; an inscribed or painted symbol considered to have magical power. See the “Sigil of Scoteia” in The Cream of the Jest: A Comedy of Evasions which Thorne and Lloyd reveal as another of Cabell’s puzzles.

Additional resources

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics: Fourth Edition