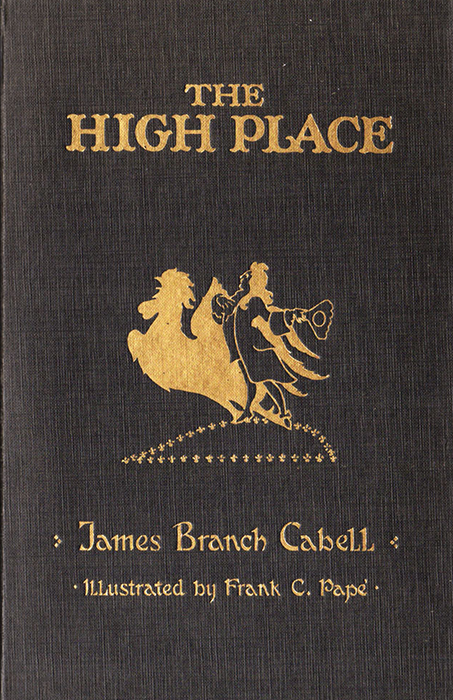

Image: Courtesy John Thorne and William Lloyd, The Silver Stallion

This essay by Stephen R. Wetta, Ph. D. was awarded the first Annual Cabell Prize in 1998.

Stephen R. Wetta is a native of Richmond who received his Bachelor’s Degree from Virginia Commonwealth University, and his M. A. and Ph. D. in English at New York University. Wetta is currently Professor of English at Hunter College.

In the spring of 1998 he successfully defended his dissertation, Artful contamination: Genre and the novel in the Works of James Branch Cabell, 1919-1927. Wetta used the work of literary theorist and philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin to examine James Branch Cabell’s writing. The essay below is one chapter from that dissertation. Stephen Wetta has had two other chapters from his dissertation published — one in the Winter 1996 issue of Southern Folklore and the second (“Epic and Novel in Cabell’s Silver Stallion) in the Fall 1997 issue of Southern Quarterly.

Permission to use this essay in any form must be made by Stephen R. Wetta.

Hagiography and The High Place

Stephen R. Wetta, Ph. D.

I

The role the fairy tale plays in James Branch Cabell’s The High Place is apparent from the very beginning: Florian de Puysange, the protagonist, sits under the “tree from the East” in the gardens of Storisende, his ancestral house, reading a “curious new book, by old Monsieur Perrault of the Academy” (4). The allusion to Perrault foreshadows what follows. Florian meets a figure from folklore and romance, Mèlusine, who gives him a vision that will haunt him for the rest of his life-a vision of her sister, Melior, and of her parents, King Helmas and Queen Pressina, and of the people and of the creatures of the castle where Mèlusine grew up, all in the depths of a sleep that has lasted for centuries because Mèlusine has put a spell on them. Florian finds the vision enchanting, particularly that of Melior with whom he instantly falls in love, and it reminds him of “a fairy tale such as those which he had lately been reading…” (8). Melior is Florian’s Sleeping Beauty; he dreams of releasing her from the spell and making her his wife.

The fairy tale thus makes a prompt appearance on the scene of The High Place. Yet the presence of a saint-Hoprig-who slumbers near Melior, and who is to determine much of the narrative’s direction after Florian effects the disenchantment of the sleeping court, signals the intrusion of another genre, hagiography, which also becomes deeply involved in shaping and structuring the novel-a fact often overlooked by critics who concentrate on the fairy tale elements in the story. Fairy tale, saint’s life and novel all blend together, each imparting their own generic characteristics to the narrative- characteristics largely defined by the different chronotopes to which each belongs.

“Chronotope” is a term M. M. Bakhtin used to describe the interconnectedness between time and space in literature. Time congeals and thickens in literature-“takes on flesh”-and gains visibility; space responds in turn to the particular representation of time in a given work. The way space and time intersect and rebound varies from work to work but nevertheless exhibits certain similarities and likenesses within genres. In his essay “Forms of Time and Chronotope in the Novel,” Bakhtin shows how different kinds of novels utilize time and space with their own particular generic significance. The adventure novel of the ancient Greeks with its highly formulaic boy-meets-girl plot, is distinguished by its strictly episodic temporal structure. One adventure follows another in sequence; yet the order of these adventures is not really fixed, since none effects any particular change in the hero and heroine. The protagonists are the same at the end of the novel as they are at the beginning, and since the end is generically predestined-marriage after enforced separation-the point of the adventure novel is adventure itself. Time has no biographical significance, and space itself is abstract and featureless, with landscapes designed so as not to hinder the unfolding of adventure time. (86-110)

Bakhtin demonstrates how time and space take on other characteristics when we turn to different examples of the developing novelistic genre-how it becomes possible to talk about the Bildungsroman, for instance, or the historical epic; and how within novels themselves chronotopes exert a shaping influence on their structure-the chronotope of the road, or the chronotope of the threshold. As the novel progresses over centuries, we see biographical time and historical time exerting more influence on narratives in patterns of increasing complexity.

The opening pages of The High Place present characteristics of a chronotope Bakhtin discusses at some length in this essay-the idyllic chronotope. Yet we should immediately point out that chronotopes peculiar to the fairy tale and saint’s life intrude upon the narrative, altering the idyll and significantly affecting not just Florian’s destiny but the very image he should possess as a figure formed by the idyllic chronotope. It is safe to say that in The High Place not one but many chronotopes are active, a situation not uncommon to the modern novel, which, because it is still evolving, may not even be a genre at all, as Bakhtin sometimes argued. The modern novel, indeed, seems to be a playground for chronotopes that come from all genres. As Bakhtin says, “Within the limits of a single work and within the total literary output of a single author we may notice a number of different chronotopes and complex interactions among them ….[I]t is common moreover for one of these chronotopes to envelope or dominate the others …. Chronotopes are mutually inclusive, they co-exist, they may be interwoven with, replace or oppose another, contradict one another or find themselves in ever more complex interrelationships….The general characteristics of these is that they are dialogical (in the broadest use of the word)” (252). It is Cabell’s distinction that, more than many modern authors, he found ways to draw on chronotopes peculiar to different genres and bring them into dialogue. As a result, his characters are always finding themselves in unfamiliar time-spaces where they must seek new means of response to generic categories completely alien to them.

In The High Place, Florian is propelled from his idyll into the chronotopes of folklore and hagiography, and ultimately wrestles with dilemmas more suited for a character in modern fiction. Specificity of time and place in The High Place impart to it a rootedness missing from most other books in the Biography. In the idyllic chronotope, time and space have a A special relationship…an organic fastening-down, a grafting of life and its events to a place, to a familiar territory with all its nooks and crannies, its familiar mountains, valleys, fields, rivers and forests, and one’s own home” (Bakhtin 225). This creates a place defined

…by the age-old rooting of the life of generations to a single place, from which this life, in all its events, is inseparable. The unity of place in the life of generations weakens and renders less distinct all the temporal boundaries between individual lives and between various phases of one and the same life. The unity of place brings together and even fuses the cradle and the grave (the same little corner, the same earth), and brings together as well childhood and old age (the same grove, stream, the same lime trees, the same house), the life of various generations who had also lived in that same place, under the same conditions, and who had seen the same things. This blurring of all the temporal boundaries made possible by a unity of place also contributes in an essential way to the creation of the cyclic rhythmicalness of time so characteristic of the idyll (225).

Readers familiar with the different volumes of the Biography know that Cabell’s novels are, like Faulkner’s, fixed in a particular region of earth, in this case, the fictional French landscape of Poictesme. And Florian is a direct descendant of the eponymous hero of Cabell’s most notorious novel, Jurgen, as well as Manuel, the progenitor of the entire Biography. The opening pages of The High Place are strongly infused with a sense of place and of the generations that have gone before. The little tree from the East under which Florian reads his book by Perrault was brought to the garden at Storisende by “his great-uncle, the Admiral…from the other side of the world.” (10) The description of the garden recalls Keats’s “To Autumn”-“this October afternoon was of the sun-steeped lazy sort which shows the world as over satisfied with the done year’s achievements” (3)-and itself mirrors the abundant race of Puysange, mellow, fruitful and overripe. When Florian awakes from his vision of Melior, his father appears by the tree and invokes for his son the memory of Jurgen and other ancestors as exemplars of discreet erotic maneuvering and political ambition. The secret of the race’s success, his father explains, is its adaptability to the changing moral and social climate at court. The Duke himself has “kept touch with his times. Under the Sun King’s first mistress Gaston de Puysange had cultivated sentiment, under the second, warfare, and under the third, religion” (11). But this is merely reflective of the essential unchangingness of the race of Puysange, the result of generations of breeding and handed-down wisdom. By adapting these various guises Florian’s father has not betrayed anything essential. A Puysange must adapt so as not to change. The Duke explains to his son the “great law of living” by which the race of Puysange has prospered: “Thou shalt not offend against the notions of thy neighbor” (23). The very landscape around Florian reflects the solidity of this tradition, and he can’t help but be aware that the house and gardens contain the forces that molded and created his race. “I am a Puysange,” he haughtily reminds those who doubt him during the course of the novel. The race is ardent, fertile, true to its word-and therefore so is he.

Because Florian remains true to his race, the father is not surprised to learn of his son’s dream about Melior. The Puysanges are a race of dreamers and idealists. The fairy tale vision of Melior itself fits into the idyll, since, Florian’s father explains, A… it is the dream which comes in varying forms to us of Puysange, the dream which we do not ever quite put out of mind. So Melior, it may be, will remain to you always that unattainable beauty toward which we of Puysange must always yearn…” (14). The ardent and active race from which Florian sprang has always dreamed of Melior, and dreaming under trees in the lazy October sun is to be expected of a character who has been formed and fashioned by this particular idyllic chronotope.

Time and place are weighted with specificity when The High Place begins. It opens in 1698-one year after Perrault published Histoires ou contes du temps passé- and quickly advances to 1723. Although the setting is the fictional Poictesme, the boy Florian is a subject of King Louis XIV, and the old Sun King’s passing is referred to later in the novel. Historical personages such as Madame de Maintenon and the Duke of Orleans enter the story. Unlike the generically named fairy tale hero, Florian is inundated with titles that point to the historical and biographical specificity of his name-Prince of Lisuarte, Duke of Puysange. Poictesme retains the feudal remnants of regional eighteenth- century France, the mores and manners of the ancien régime. The opening pages of The High Place, then, present Florian as a character whose image and identity have been formed by the chronotope to which he belongs. “The chronotope in literature,” Bakhtin writes, “has an intrinsic generic significance….The chronotope as a formally constitutive category determines to a significant degree the image of man in literature as well. The image of man is always intrinsically chronotopic” (84-85).

At the same time, the chronotope of the fairy tale intrudes on the narrative and indeed determines the direction it will take. The opening scenes prepare us: a boy learns of an enchanted Sleeping Beauty and undertakes her rescue, after encountering many dangers along the way. Otherworldly aid-from Janicot, in Florian’s case-comes to the boy and he uses it wisely to accomplish his task. Florian, in fact, plays a familiar fairy tale role-that of the disenchanter who releases a group of victims from an evil spell.

More important, the primary fairy tale impulse causes Florian to leave his idyllic chronotope, to wander out into unknown generic territory. A signal characteristic of the idyll, after all, is that everything happens within its peculiar space. The idyll is a limited world of family connections and well-defined landscapes. The protagonists experience all their adventures within the familiar landscape of home.

Florian thus demonstrates characteristics common to both the idyllic novel and the fairy-tale. His rootedness and sense of tradition bind him closely to the plot of land his family has inhabited through the generations; yet he leaves this world for a magic world of enchantment and adventure. And a certain tension between the genres is inevitable, since the idyllic image from which Florian draws-or should draw-his most pronounced generic characteristics contrasts strongly with the image of man as developed in the fairy tale chronotope. The time and space of the fairy tale hero, for instance, have no biographical or historical significance. Kingdoms are almost never named, even when the hero is a prince or princess. The hero has no private space, does not really belong to any place or to anything, is aware of no attachments to home. Time in the fairy tale corresponds to this spacial anonymity. It is common, as everyone knows, for fairy tales to open with the words “Once upon a time,” and the article clearly renders the time general and unspecific. The impression is that the fairy tale happens in some prehistoric past-before dates, before national and racial boundaries give geographic and historic specificity to the world, before even proper names are important. As Joyce Thomas Sheffield observes, the hero is given a generic name rather than a family name, and this tends to detach him further from a specific time and place and adds to the impression of freedom surrounding him-he is a person to whom anything can happen (30-31).

Max Lüthi has shown that the fairy tale hero is almost always a wanderer. He leaves home and rarely returns; from his wandering he gains a precious “impression of freedom” (Once Upon A Time 140-141). He is also a loner who forms attachments as readily as he dissolves them. As the hero wanders, helpers appear, serve their purpose, then disappear. As Lüthi notes, “[The hero is] one who, though not comprehending ultimate relationships, is led safely through the dangerous, unfamiliar world” (142). The hero is “gifted,” in Lüthi’s terminology-that is, possesses a kind of charisma that makes his behavior “unconsciously correct” (142) and deserving of miraculous intervention. The isolated and helpless status of the hero is, therefore, not a misfortune rather, it is part of his special gift for freedom, and renders him able to enter quickly into new relationships without ever becoming tied down.

What role do these characteristics play in determining the development of Florian’s character? One of his more remarkable characteristic is his isolation from other characters in the novel, his determination to carry events to their destined conclusion at no matter what cost. He shows no loyalty to those who share his idyllic time-space, and he is characterized by a restlessness peculiar to an idyllic hero. Other Puysanges have merely dreamed of Melior, but Florian actually arms himself with sufficient magic to approach her and to disenchant her.

We quickly learn of the ease with which Florian “dissolves” attachments: as he grows older, before he embarks on his journey to Brunbelois and The High Place, he marries four times. At the beginning of the third chapter, he is engaged yet again, and, indeed, it is to this betrothed that he is riding when he encounters Janicot in the woods. We further learn that Florian has murdered his ex-wives without the slightest twinge of conscience, and that he is similarly about to dispatch his homosexual lover, Gian Paolo. Like many fairy tale heroes, Florian is indeed an isolated and alone figure (although he increasingly resembles, as the narrative progresses, the antagonists of fairy tales rather than the heroes- Bluebeard rather than Hans.) And, of course, he is undertaking a task familiar to readers of the fairy tale, disenchantment -rescuing his princess from malicious witchcraft and marrying her.

Yet the pronounced specificity of Florian’s time-space and the influence it has had on forming his image render him a singularly unlikely fairy tale hero. And he departs from the image of the hero in significant ways. For one thing, although he eventually functions in the narrative as a character who is given a fairy tale task, he first appears to us as a reader of fairy tales. He is therefore inside and outside the tale, and the double perspective gained from this position serves to destroy his suitability as a fairy tale protagonist. His every action is undertaken with a consciousness of how other fairy tale heroes perform-a consciousness which in itself undermines his effectiveness as an actor. As V. Propp has demonstrated, “The question of what a tale’s dramatis personae do is an important one for the study of the tale, but the question of who does it and how it is done already fall within the province of accessory study” (Morphology 20). In strict structuralist terms, the fairy tale hero is little more than a function of narrative, whose basic role is to act and react. Florian’s self-consciousness makes him, like Manuel before him, too reflective for the fairy tale-too much caught up in who he is, and how he is to perform his task.

In the very opening pages of The High Place, then, contamination has already occurred. Two chronotopes, those of the idyll and the fairy tale, commingle on the same page with the result that the reader experiences neither one genre nor the other, but participates in a dialogue between them.

When we come, in Chapter Three, to the scene of Melior’s disenchantment by Florian, we have arrived where most tales end, at the point where the hero and the princess live happily ever after; but this is precisely where, in a sense, this novel begins. Idyll and fairy tale have mixed so thoroughly that the result is, for the reader, a peculiar sense of familiarity and strangeness. Somehow both are exerting influence on the narrative, yet neither really remains strong enough to impose its own generic restraints on its structure. By the time Florian has disenchanted Melior, neither the idyll nor the fairy tale possesses stamina enough to play a major role in the progressing narrative.

It is here that we should turn our attention to another genre involved in the narrative-the saint’s life.

II

The High Place is subtitled “A Comedy of Disenchantment,” underscoring the fairy tale role Florian initially plays. Yet there is another sense of “disenchantment” which certainly is implied as well-disillusionment, as when someone or something loses its appeal; consequent boredom, disappointment, loss of interest. For Florian, this means that no sooner does he gain Melior than he wants to be rid of her-he finds her trivial, boring, trite, loquacious. Florian has, in other words, become disenchanted himself, and is himself in need of magic and intervention.

In proportion to the growing influence of hagiography on the narrative, the role of the fairy tale dwindles. Indeed, it might even be said that the fairy tale merely contributes an introductory function to the generic dialogue: Florian’s impetus to leave the idyll. From this point on, the saint’s life occupies an increasingly prominent role, especially after the character of Hoprig enters the novel. The role hagiography plays in The High Place might be more apparent if we first examine a legend found in Jacobus de Voragine’s life of St. Basil which, for the sake of brevity, is here paraphrased:

They say there was once a wealthy man named Heradius who loved his daughter and wanted to consecrate her to the Lord. One of his slaves was overcome by passion for the girl and contacted a sorcerer to aid him in seducing her. The sorcerer gave the slave a letter and instructed him to stand on a heathen’s tomb at midnight to summon the devil. The slave did as he was told and met with the devil, promising to serve him for eternity in exchange for possession of the girl. The girl immediately fell madly in love with the slave and begged Heradius to let her marry him. When she went so far as to threaten suicide, the reluctant father agreed to the wedding. Soon, however, the girl noticed that her husband refused to enter a church or make the sign of the cross. Her husband protested his innocence when she asked him about his behavior, but the bride went to see Basil, the Bishop, and confessed her troubles to him. When Basil interviewed the husband, the truth came out: the ex-slave insisted that he wanted to live a Christian life but could not because his soul belonged to the prince of darkness. Basil led the tormented man to a cell, locked him in and began to pray for him continuously. The demons attacked the man, but soon their tortures lessened. Basil released the ex-slave from the cell and took him to the church. There, in front of the entire congregation, he completed the exorcism. The howling demons were expelled, and Basil made the man worthy once again to receive the sacraments.( 1: 110-12).

Like the slave in the legend attached to Basil, Florian compromises himself by accepting the aid of demonic powers to win Melior, and it is in the crisis of his moral disenchantment where the novel finds its theme.

This disenchantment begins twenty-five years after the novel opens, when Florian encounters a demon named Janicot in the forest of Acaire while he is journeying to marry his fifth wife. Janicot convinces him that he can possess Melior if certain rituals are performed, such as, for instance, making a sacrifice of their first-born in a year’s time, assassinating the most powerful man in the kingdom, and accepting that Melior will vanish at the end of the year. Added to this considerable price is the certainty that the insult to his current betrothed-who happens to be the sister of his brother’s wife-will provoke his brother to duel with him. Nevertheless, Florian agrees to the terms, journeys to Brunbelois with the appropriate charms for overcoming the monsters who guard the castle, and releases Melior and the others from their centuries’ long sleep. After he marries Melior their happiness is brief, and she soon learns the price Florian has to pay for their time together. Melior entreats Hoprig, their patron saint, to rescue them from the terms of Janicot’s contract. Hoprig confers secretly with Melior, gives her a magic ring and duly performs the necessary rites to thwart Janicot.

It is here that the hagiographical elements begin to dominate the novel.

The saint frequently acts, like the fairy tale hero, as a disenchanter. For example, Basil releases the slave from the devil’s clutches, just as other saints regularly perform exorcisms, free victims from spells, and reverse charms by employing otherworldly aid. In The High Place, Hoprig’s task is to disenchant the disenchantment, to restore order to a world (Florian’s) founded upon ideals of beauty and holiness. Hagiographical motifs organize the novel and serve to foster a dialogue between the disillusioned modern world Florian has inherited and the older tradition of love and sanctity which has been preserved in the slumbering castle at Brunbelois. Since he figures so prominently in the novel and brings his own peculiar chronotope into it, we should take a moment to examine Hoprig more closely.

The legend of Hoprig goes as follows: “untoward circumstances” caused him while yet a baby to be placed in a barrel and released upon the sea, where he floated aimlessly for ten years, fed through a bunghole in the barrel by an angel. When the barrel finally washed up on shore ten years later, it was discovered by a fisherman, whom Hoprig instructed to go forthwith to a nearby monastery and bid the abbot to come and baptize him. There followed a lifetime of “miracles and prodigies” as Hoprig traveled the land, converting the heathen and overcoming evil. Finally the saint arrived at the court of Helmas, Melior’s father, and “wrought miracles there also, to the discomfiture of the abominable Horrig [the heathen high priest].” We find, when the novel begins, the ten- year-old Florian reflecting on the “beauty and holiness” of Melior and Hoprig slumbering side-by-side at Brunbelois, reflecting “with a dumb yearning to be not in all unworthy of these bright, dear beings” (16-17). As Florian grows into an adult, he tenders constant prayer and homage at the church of Holy Hoprig, asking respectfully for the saint’s intercession and guidance.

It is when he grows up-after he has disenchanted the court at Brunbelois-that he learns the dreadful truth. The supposed pagan high priest, Horrig, was actually the saint upon whom Hoprig’s legend is based, and the two men became confused when the tail on the first “R” in Horrig’s name was worn away from his tombstone by the elements. Hoprig, who was in reality the High Priest of a pagan sect, the Llaw Gyffes, was canonized by accident when miracles began occurring at Horrig’s tomb. Meanwhile he has been slumbering for centuries under Mèlusine’s spell along with Melior, Helmas and the rest of the court at Brunbelois. Now disenchanted, Hoprig realizes he is a Christian saint crowned with a halo, and dutifully attempts to meet his new sacred responsibilities. Florian, meanwhile, despairs because all his prayers and entreaties over the past years have been wasted on the wrong saint.

In Hoprig’s story there is irony, no doubt, but it should be emphasized that Cabell’s apparent sabotage of the hagiographical tradition is not as subversive as it might at first seem. No doubt this is the kind of irony his readers expected of him and helps to explain why he has so often been attacked for his apparently empty cynicism. Yet mere parody is not his intention here so much as the testing of ideals that actually mean something to him. Cabell is true to the genres which he mines for his own purposes. And the dubious circumstances leading to Hoprig’s canonization reflect genuine difficulties and doubts peculiar to the special needs of the hagiographer, such as determining just who the real saints are, and what makes them saints.

In real hagiography, for instance, we do find uncertainty over what exactly establishes sainthood, an uncertainty that often caused considerable conflict between local communities and the papacy. As Aviad M. Kleinberg has demonstrated, hagiography and its practitioners found themselves, as the Christian era progressed, with an ever- expanding “repertoire of saintly behavior” (37) to consider. Over the centuries, hagiographers and those officials responsible for canonization discovered that “old definitions [of saintly behavior] were too narrow and needed reinterpretation” (36). The desire to satisfy local communities would at times lead the church, for political reasons, into hasty canonizations. Theologians such as Augustine further complicated matters: he argued that judging the outward behavior of a person is not an adequate means for determining sainthood, since only God knows what is in a person’s heart. More to the point, Augustine’s “notion that without divine inspiration empirical evidence was no more than a tentative indication of a person’s sainthood was generally accepted. Theologians had to concede not only that some saints remain unknown to the church, but also the more annoying possibility that some nonsaints are venerated as saints” (22-23).

There is, for example, in Sulpicius Severus’s “Life of St. Martin of Tours” an incident recounting Martin’s skepticism about the veneration the people of a certain town were showing at a place where martyrs were supposedly buried. Martin had “grave doubts of conscience” about this veneration, since “no certain and settled tradition had come down to them” (Noble and Head 14). Finally he went to the place himself and prayed to the Lord to make the truth known, and eventually a ghost appeared, “foul and grim,” and confessed to a wicked past. “He had been a robber, and had been executed for his crimes, but had become an object of devotion through a mistake of the common people” (14-15).

The story of Hoprig, then, illustrates that sainthood is more a matter of local or ecclesiastical perception than verifiable truth. It also points to one of the more uncomfortable consequences of hagiography, which is that nonsaints frequently become canonized and, conversely, those deserving of canonization are just as often overlooked.

To Hoprig, however, the issue isn’t really that grave. Attempting to comfort Florian, he instructs him in the precedents of false canonization, since he well knows that precedents justify everything for his protégé. “St. Hippolytus, who never heard of Christianity, since he lived, if at all, several hundred years before the Christian era, was canonized by mistake. St. Filomena’s legend rests upon nothing save the dreams of a priest and an artist, who were thus favored with unluckily quite incompatible revelations. The name of St. Viar was presented for beatification because of a time-disfigured tombstone, like mine, a stone upon which remained only part of the Latin word viarum: and two syllables of a road-inspector’s vocation were thus esteemed worthy of being canonized… “(182). The list goes on, and finally Hoprig sums up with an instructive moral: “We must zealously preserve those invigorating stories of the heroic and virtuous persons who lived here before our time so gloriously, because people have need of these excellent examples” (190). We are dealing here with a theme central to the Biography- which is that all is literature, and what matters in literature is not what is true or false, but what is believed.

What is most distressing to Florian, however, is that Hoprig takes his new duties seriously and has every intention of preserving the soul of both Melior and himself for the Lord. Hoprig thus exhibits a trait quite typical to characters in Cabell’s novels: he feels obligated, however unsuited he really is, to behave according to his generic bonds. Having started his career as a pagan adventurer, Hoprig finds himself the protagonist of a Christian legend and immediately undertakes to act accordingly. But how does a saint behave? What are the features peculiar to the saint’s life?

In “Forms of Time and Chronotope in the Novel,” Bakhtin shows that time and space in the genre of the modern novel are mainly biographical-that is, the significant biographical moments of the protagonists consume the temporal and spatial structure of the work, determine its depth, pace, and focus. Other factors come into play, depending on the complexity of the individual work-i.e., the historical setting, the geographical setting, etc.-but essentially the modern novel has become deeply involved with the biographical growth of the hero. What distinguishes “the image of man” in hagiography from that of the modern novel is the former’s concentration on a crisis in a character’s life, a crisis that transforms him from one type of person to another. (In this respect it bears similarities to the menippea.) In other words, hagiography forgoes “biographical life in its entirety” [Bakhtin’s italics] to present “as a rule only two images of an individual, images that are separated and reunited through crisis and rebirth: the image of the sinner (before rebirth) and the image of the holy man or saint (after crisis and rebirth)” (115). In Hoprig’s case, the reader experiences two images-the demonic leader of the Llaw Gyffes, and the patron saint of Florian’s church.

Yet these exceptional moments in a saint’s life are, or should be, emphasized for purposes of moral instruction. The person is not as important as the saint, and hagiography is not biography in the modem sense. Although, as Kleinberg shows, “hagiographers expect to be believed on some level” (52) and wish to convince the reader of their sincerity, saints, especially the older saints whose acts had become a matter of tradition, “could be made into an ideal stereotype. [The personality of the saint]…could merge into the quality of sainthood that is nonspecific and unquestioned” (53). And this is no doubt responsible for the sameness that many readers find in the lives of the saints. Stereotypical sanctity in hagiography exists to strengthen the faith of its readers, to affirm their belief in the miraculous powers of God and the possibilities of Christian virtue.

In The High Place, no sooner does Hoprig learn of his canonization than he becomes determined to conform to hagiographical stereotypes. Yet if, as Bakhtin insists, the concern of hagiography is “the testing of an idea and its carrier, testing by means of martyrdom and temptation,” then Hoprig plainly falls short, since he has earned the status of saint through no virtue of his own-without struggle, doubt or affirmation. We see him before and after rebirth, but the crisis which divides the two states is missing. Hoprig does not possess, then, the characteristics required of the saint’s life chronotope. If the hagiographical influence on the novel ended with Hoprig’s character, then The High Place would indeed have been guilty of borrowing from the genre merely to parody it.

Yet Hoprig, by injecting the idea, of the saint’s life into the novel, sufficiently contaminates it to allow the genre to exert its own gravity on the course of the narrative. And we find that the testing and the crisis which Hoprig should have undergone is experienced instead by Florian, who, in so many ways a character with the generic qualities of the idyll, nevertheless acts according to motifs we find in the saints’ lives.

The dream vision Florian has of Melior, for instance, is common to medieval romance and hagiography. In Christian literature, the vision often comes as a form of temptation, such as that experienced by Christ in the wilderness. Just as often, however, it can be a beatific vision that motivates the protagonist from the moment of vision forward, that sends him into the moral and spiritual testing ground of hagiography. We find in the “Life of Laurence Justiniani” by Sabine Baring-Gould-a writer whom Cabell frequently used as a source for his allusions-the following incident:

One night, when he was nineteen years old, he had a dream, in which he saw the Eternal Wisdom manifest in human form as a maiden in dazzling raiment, and heard her say, “Why seekest thou rest outside of thyself’? Enter within, and seek peace in thine own soul. Seek it in me, who am the Wisdom of God. Take me for thy spouse, thy portion, and the lot of thine inheritance.” The dream produced a lasting effect on his mind, and he made the resolve to devote himself to God alone (77).

Florian, like many saints, is enamored of ideals that come to him in the form of a vision early in life to haunt him and drive him restlessly forward, creating a deep dissatisfaction in him with things of the world. The ideals of beauty and holiness in particular are represented by his vision of an enchanted High Place where Hoprig sleeps peacefully near his beloved Melior.

In many respects, the worldly life Florian lives as he grows older conforms to hagiographical patterns. This life, defined by its sensuality and reliance on sensation and mental distraction, leads ultimately to profound dissatisfaction. The saint becomes aware of an acute inner emptiness and seeks salvation. The most famous example of this kind of life in Christian literature is provided by Augustine, yet it is common to almost all saint’s lives. The fundamental difference between Florian and the saints is that the latter find fulfillment in their visions and ideals, whereas Florian only finds despair.

Yet even here Florian behaves according to hagiographical patterns. His eventual disavowal of Melior is strikingly similar to acts of worldly and carnal renunciation undertaken by the saints, which most commonly take the form sexual disgust. St. Bernard, for example, frequently found himself in sexually compromising situations because his good looks inspired lustful thoughts in women. One evening, according to Voragine, a woman at whose house Bernard was staying climbed into his bed and attempted to make love to the saint. Bernard’s response was to rouse the household by crying out “Thieves! Robbers!” Later he explained to his traveling companions, who seemed somewhat amused, “I really faced a thief’s designs on me last night, because my hostess tried to rob me of my chastity, a treasure that, once lost, can never be recovered” (2:99). Donald Weinstein and Rudolph M. Bell have shown that many saints, particularly from the aristocracy, were forced into unwanted marriages; many found that their marriages tempted them away from their spiritual callings. It was not uncommon for male saints to persuade their wives to enter the cloister (73-99).

Most saints found conjugal life too distracting, and many of their unions were not consummated, or were consummated only to fulfill what is sometimes called the “marital debt” of 1 Corinthians 7, which justified procreation, and even made it mandatory: “Let the husband render to his wife what is due to her, and likewise the wife to the husband” (see Noonan 284-286).

Florian’s own marital debt is included in the contract he has made with Janicot: a first-born must be conceived in order to be sacrificed. But no sooner has he impregnated Melior than he leaves the castle, only to find excuses to keep from returning to the embraces of the woman he now hates. Affairs with other woman from this point on serve merely to remind him that with Melior he attained all that can be desired by any man on earth: “He found in no tête-à-tête, and through no personal investigation, any beauty at all comparable to the beauty of Melior. This much seemed certain: she was the most lovely animal in existence. But one must be logical. She was also an insufferable idiot: she was, to actually considerate eyes, a garrulous blasphemer who profaned the shrine of beauty by living in it: and Florian was tired of her, with an all-possessing weariness that troubled him with the incessancy of a physical aching” (196-95).

Florian’s marital accord in its own way conforms to saintly behavior: he performs his “debt,” and then terminates all physical relations with his wife. The very thought of sexual intercourse with Melior now sickens him and he reacts with loathing to her pregnant body: “His disenchanted princess now was hardly recognizable. Her face was like dough, her nose seemed oddly swollen; under and about the blood-shot eyes were repulsive yellow splotches. As for the bloated body, he could not bear to look at it. He was shaken with hot and sick disgust when he saw this perfectly dreadful looking creature” (219).

Such distrust of women’s beauty, such disaffection with erotic attraction, such downright misogyny, all can be found in hagiography. St. Gerald of Aurillac’s hagiographer tells us that the devil tempted the saint with “the instrument of deception by which Adam and his posterity are most often led astray by mean woman.” Satan brings a woman before Gerald, who immediately finds himself “tortured,…allured, and consumed by a blind fire.” Overcome, Gerald sends for the girl, then realizes what he has done and prays to God for help. When she arrives, “…this same girl appeared to him so deformed that he did not believe it was she whom he saw… Gerald understands that the mercy of God altered his perception of the girl: “Perhaps he who had allowed himself to be on fire for a whole night, was now assailed by too great coldness, that a harsh frigidity might punish the warmth of a slight delectation” (Noble and Head 304). Augustine was so terrified of the attraction of women, according to Possidius, that he even refused to allow his sister or his nieces to stay in the same house with him lest this “might give scandal or prove a temptation to the weak” (ibid. 58). Misogyny is a staple of the male saint’s spiritual diet. Since Melior is for Florian the ideal woman, the Eternal Feminine, his loathing for her represents the renunciation of Woman Worship, or what Cabell usually called “Domnei.”

But how does this affect Florian, and in what ways can he be said, from this point on, to resemble the saint? We have seen how, according to Bakhtin, the chronotope of hagiography can be divided into two: the life before spiritual rebirth and the life after. The chronotopes that can be found in The High Place are affected in significant ways by those of other genres. First, the fairy tale chronotope impels Florian outward, and the idyllic chronotope to which he belongs in the beginning of the book is shattered. Yet, as we have seen, the fairy tale affects the narrative very little from this point on; Florian is straddling the borderline of two chronotopes now: that of hagiography and that of the modern realistic novel, with its disaffected hero embarking on an epistemological quest. What we should expect to find in the latter case is a narrative involving the entire life of the hero, encapsulated perhaps in a specific period of time, but concerned, nevertheless, with all the elements of space and time that influence the development of character-the hero of the modern novel is placed in historical time, we see social and environmental forces working on him, we see him responding to these forces concentrated in a particular space. Hagiography, on the other hand, focuses on moments specific to two particular aspects of character-before and after. Biographical time is bifurcated and specialized, and the spatial field of the narrative is narrowed to highlight the moral and spiritual excellence of the hero.

In The High Place, hagiography performed its own bifurcation on the narrative: we see Florian under the spell of the enchanted vision, and Florian after the disenchantment has been performed. We encounter Florian at the age of ten, and the disillusioned Florian of thirty-five. Biographical time is concentrated on the two relevant aspects of his character: Florian the believer, and Florian the disenchanted. Yet we notice that, here the traditional hagiographical values have been reversed: Florian is converted from faith to despair. This is the design of the hagiographical chronotope, but not what the chronotope was designed to do. We find in the post-conversion Florian, instead of a saint, an anti- saint, and one whose direst enemy is Hoprig, the canonized representative of the church. This is where the chronotopes of hagiography and the realistic modern novel enter into a contaminated relationship. It is in the post-conversion Florian that we find a modernist hero.

III

What is Florian’s faith? It he code of the Puysanges is “Thou shalt not offend against the notions of thy neighbor” (23). What the Puysanges share in common with the best saints is a belief that the true armor of the superior individual, is manifest humility-a conscious effort not to show off one’s superiority.

Yet it is in how Florian defines superiority that he finds his difference from the saints, for his values are aristocratic and gallant; they have nothing in common with the virtues of the Christian mystics. Florian’s determination to honor the terms of the pact with Janicot, for instance, does not arise out of a love of virtue for its own sake, nor even for Christ’s sake. It is simply that as a Puysange, he stands by his word: this is the pride of his race. He will stand by his word even if it means, eventually, murdering his brother and his good friend, the Duke of Orleans. Florian stands by his word even when he discovers that his patron saint is not really a saint and that the woman who has always represented to him the highest ideal of beauty and perfection is now physically and morally repugnant to him. In the face of the disintegration of everything he has ever honored or believed, when, one supposes, he might be most tempted to give in to the temptations of nihilism, Florian doggedly goes through the motions of honoring his word, as if Hoprig really is a saint and as if the attainment of Melior still means something to him. Florian’s resolve to remain true to the terms of his pact, to act “as if,” to attempt by his actions to render meaning to a world now meaningless, decisively projects him out of the fairy tale, the idyll and the saint’s life, and establishes him as hero of the modernist novel.

Those other genres are, after all, essentially modes of affirmation. The hero of the fairy tale is “gifted,” as we have seen-he possesses remarkable charisma, is watched over by otherworldly helpers who lead him through treacherous landscapes, and attains his goal by virtue of his very status as hero of the tale. The idyll, too, affirms tradition and stability, the rightness of being rooted in a single place on earth, of inheriting the wisdom of the generations. Hagiography, of course affirms Christian grace; affirms, as Thomas Heffernan put it, “the medieval understanding that the saint’s life is the perfect imitatio Christi” (20). None of these genres is concerned with matters of belief and faith except as affirmation; epistemology is not really their concern. Yet epistemology is the dominant discipline of the novel (Bakhtin 15). The novelistic hero exists to seek rather than find, to question rather than affirm. As such, he is a transcendent character who rises above dialectic into the reaches of dialogue; he is characterized by his openness and his refusal to be contained within the limits of genre. And this very openness distinguishes his approach to ideal categories. “Faith” is not, for the novelistic hero, a matter of affirmation, nor even one of denial. The very word, being dialogically informed, contains both affirmation and denial, yet favors neither; it is ever evolving, with the capacity to be discovered over and over again by each new approach. As a dialogical term, “faith” is, quite simply, full of irony.

Many critics have found similarities in spirit between the novels of Cabell and the modernist philosophy of Santayana. Arvin R. Wells, quoting Joseph Wood Krutch, notes that the essence of this particular kind of modernism lay in a sort of “ironic belief …a determination to act as though one still believed the things that were once held true” (13). Modernism, according to Santayana, “is the love of all Christianity in those who perceive that it is all a fable. It is the historic attachment to his church of a Catholic who has discovered that he is a pagan” (quoted in Wells 21). Wells adds, “It is, in other words, a delicate equilibrium wrought by the intellect which allows one simultaneously to perceive that ideals and religious concepts are from a scientific point of view merely fabulous, and yet to value them for their poetic power, that is, their power of evocation and harmonization and their power to make us by anticipation citizens of a better world” (21). To idealize life in an age of shattered idealism-that is the essence of the modernist spirit, and no one exemplifies this power better than Cabell with his pantheon of ironic believers.

In Florian’s case, the battle is almost lost. Hoprig’s cynical determination to carry on as a saint even when he knows for certain he is not causes Florian to doubt the very state of saintliness. And his doubts reflect the discontinuity between an age of saintliness and the modern world-a discontinuity perhaps best summed up by the twentieth- century Romanian philosopher E. M. Cioran, who in his meditation on saints and saintliness had this to say:

Saintliness would be a most extraordinary phenomenon, even more than divinity, if it had any practical value. The passionate desire of saints to take over the sins and sufferings of mortals is well known. Many outbursts of infinite pity could be cited to confirm this. But in spite of all that, do the bitterness and sufferings of others diminish at all? Except for their capacity to comfort, the saints’ effort is useless, and the practical achievements of their love are nothing but a monumental illusion. One cannot suffer for another. How much can your increased suffering relieve the suffering of your neighbor? Were the saints to understand this simple matter, they would probably become politicians; that is, they would no longer be ashamed of appearances. Only appearances can be changed. But saints are politicians afraid of appearances. Thus they deprive themselves of matter and space for their exercises in reform. One cannot both love suffering and appearances at once. In this respect saintliness is not equivocal. A vocation for appearances ties most of us to life. It frees us from saintliness (12).

This “vocation for appearances” is summed up in Florian’s family’s code-“Thou shalt not offend against the notions of thy neighbor.” This is the vocation of the Puysange’s, but not of saints; from saints, Florian expects far more. His faith is thus tested most severely when he learns, in the end, that it is Hoprig and not himself who is the father of Melior’s child; that Hoprig, his patron saint, has gleefully carried out the seduction of Melior, his ideal of beauty, in order to annul the pact Florian made with Janicot to hand over his first-born. Hoprig’s unsaintly solution to the problem of Florian’s pact, so jaded in its self-interest, so dependent on appearances, coupled with Melior’s complicity in it, is too much for Florian: they have destroyed for him the possibility of belief in the ideals they represent.

He has, nevertheless, one ideal left-that is the gallant ideal of the Puysanges, their adaptability, their power to survive, their public honor. Florian’s word as a Puysange is his last resort, but it motivates him powerfully enough for the rest of the novel. He performs his duties with gallant single-mindedness, his battle now being waged against Hoprig and the meddling Christian tradition he represents, which is all the ideal of holiness has amounted to in the end. To enlist his aid in the battle against the saint, Florian turns to a mysterious otherworldly creature whose powers are “at least as strong as Hoprig’s power” (237)-the Collyn.

When the Collyn warns Florian that Melior is now under Hoprig’s protection and that fulfilling the terms of the pact with Janicot will be dangerous, Florian delivers what is in essence a modernist creed: the human determination to struggle on in spite of loss of faith and personal powerlessness. “The pious old faith that made my living glad has been taken away from me, the dreams that I preserved from childhood have been embodied for my derision….The past, wherein because of these empoisoned dreams I stinted living, has become hateful: and of my hopes for the future, the less said the better. All crumbles, Collyn: but Puysange remains Puysange” (239).

To the Collyn’s argument that Florian is clinging to one last remaining illusion, and that no illusion is better than any other, Florian replies:

If I have wholly invented it, without the weaving into its fabric of one strand of fact-why, then, all the more reason for me to be proud of and to cherish what is particularly mine. Do my dreams fail me? That is no reason why I should fail my dreams, which indeed, Collyn, have erred solely in contriving a more satisfactory world than Heaven seems able to construct (240).

Florian expresses confidence in the demiurgic powers of the mind to construct a personal, individual world that is somehow better than the world as it is. These “dynamic illusions” give humanity its peculiar persistence in the pursuit of dreams and its ability to survive in the face of seemingly insurmountable forces. To lose faith in ideals completely is to surrender-to commit a kind of psychic suicide.

We have seen that according to Bakhtin the concern of hagiography is “the testing of an idea and its carrier, testing by means of martyrdom and temptation”; what is tested in Florian’s case is not any particular ideal, such as beauty or holiness or faith, but idealism itself. Florian’s trial is to come to terms with a world that has abandoned beauty and holiness and faith, a world that offers nothing to the idealist. And Florian finds, ultimately, that humanity’s ability to persevere in a world of shattered ideals provides an idea beautiful enough to allow him to go on.

Deciding not to enlist the powers of the Collyn against Hoprig, he delivers his ultimate statement of faith:

Yes, you are free, with no claim upon me, alone of all my race, since now that I renounce good I shall put away also. For I am Puysange: I dare to look into my own heart, and I can find there no least admiration for Heaven or Heaven’s adversaries. It may be that I am fey: I speak under correction, since that is not a condition with which I have had any experience. But it seems to me that gods and devils are poor creatures when compared to man. They live with knowledge. But man finds heart to live without any knowledge or surety anywhere, and yet not go mad. And I wonder now could any god endure the testing which all men endure? (243)

Florian thus finds in his hagiographical crisis a strength which is the strength of all humanity-the strength to create again and again, upon the destruction of old worlds, new worlds worth living in.

This does not, however, mean an abandonment of traditional beliefs and ideals. Cabell’s relentless dialogical experiments with older generic forms is sufficient testimony to his need for them-to his need for the spirit which impels them and for the traditions they affirm. What the fairy tale and the saint’s life have in common is a generic structure that allows their heroes to go forth into worlds that are new while being familiar. And it is precisely this familiarity Cabell seeks to retain-the familiarity of old beliefs and ideals even when these are beginning to seem like impossibilities. This desire to bring tradition back to the disrupted world of the twentieth-century is a peculiarly Modernist desire, one Cabell shared with contemporaries such as Eliot and Pound. Frank Lenticular has demonstrated how Pound used allusion in lyric to “create…singlehandedly a traditional culture out of his welded fragments and bring it home to his time. De Born’s ‘borrowed lady,’ or, as the Italians translated it, una donna ideal e, is also a figure of Pound’s lyric practice and his desire to instigate cultural risorgimento, for America in particular. Una donna ideal e is the image of the tradition-his true Beatrice-that, particularly in The Cantos, Pound would invent by piercing together a new writing characterized by allusion, quotation, translation, adaptation, pastiche, even original writing in another language. This new poetry would be open to the inclusion of history by way of the inclusion of half- acres of document, the brute prose of chronicle that Pound jammed into the intimate rooms of his elegant lyricism” (209). Of Eliot Lenticular writes, “It is the mind of Europe that [he]…surrenders himself to, because he believes it to be more valuable than his private mind, and in so surrendering enters a community of long historical duration, as the ‘conscious present.’ This consciousness attaches epigrams to its poems…and tends to express itself in associative leaps…that defy logic and chronology because the ‘conscious present’ is aware of the past all at once, as a totality, not as a linear series of events. Allusion for this kind of consciousness is not a simple literary strategy, a knowledge of the past manipulated in the present by a writer dispassionately interested in the past, but a mode of consciousness whose nature is historical” (261).

Like his Modernist contemporaries, Cabell invokes older forms and genres not to parody them but to create a sense of continuity between the past and the present. By resuscitating old genres and connecting them, in a sense, to the life-support of the modern novel, Cabell aims to achieve the highest possibilities of dialogue. He brings up old ideals not to mock them, but to learn from them. And the object of faith is not so important to him as the fact that humanity is capable of faith. This infinite human capability for faith is, for Cabell, sufficiently awe-inspiring in itself. That man can “find heart to live without any knowledge or surety” is not, after all, the perception of a cynic. It is what Cabell has found at the heart of Western literature, an endless capacity for believing, a determination to withstand all trials and crises, a rich tradition of endurance and creativity that can, in the end, survive even the loss of saints and idylls.

Works Cited:

Bakhtin, M.M., The Dialogical Imagination. Michael Holquist, ed., Caryl Emerson, trans. (1981; Austin: U of Tex P, 1992).

Baring-Gould, S., Lives of the Saints. Vol. 10 (Edinburgh- John Grant 1914).

Cabell, James Branch, The High Place (NY: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1923).

Cioran, E. M., Tears and Saints (U of Chicago P 1995).

Davis, Joe Lee, “Cabell and Santayana in the Neo-Humanist Debate” The Cabellian, Vol. IV, No. 2, 1972.

Heffernan, Thomas, Sacred Biography (Oxford U P 1988).

Kleinberg, Aviad M., Prophets in Their Own Country: Living Saints and the Making of Sainthood in the Later Middle Ages (U of Chicago P. 1992).

Lenticular, Frank, Modernist Quartet (Cambridge U P 1994).

Lüthi, Max. Once Upon a Time: Of The Nature of Fairy Tales Lee Chaedeayne and Paul Gottwald, trans. (Bloomington: U. of Indiana P, 1976).

Noble, Thomas F. X. and Head, Thomas, eds., Soldiers of Christ: Saints and Saints’ Lives from Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (University Park: Pennsylvania State U P: 1995).

Noonan, John T., Jr., Contraception: A History of Its Treatment by the Catholic Theologians and Canonists (Harvard U P 1966).

Propp, Vladimir, Morphology of the Folktale. Louis A. Wagner, ed., Laurence Scott, trans. (Austin: U of Tex P, 1968).

Sheffield, Joyce Thomas, Inside the Wolf’s Belly: Aspects of the Fairy Tale (Academic Press 1989).

Voragine, Jacobus de., The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints Vols. I & II William Granger Ryan, trans. (Princeton U P 1993).

Weinstein, Donald and Bell, Rudolph M., Saints and Society: Christendom, 1000-1700. (U of Chicago P 1982).

Wells, Arvin R., Jesting Moses: A Study in Cabellian Comedy (Gainesville: U of Florida P, 1962).